Go Scheduler (1)

Source: Scheduling In Go : Part I - OS Scheduler

1. OS scheduler#

Your program is just a series of machine instructions that need to be executed one after the other sequentially. To make that happen, the operating system uses the concept of a Thread. It’s the job of the Thread to account for and sequentially execute the set of instructions it’s assigned. Execution continues until there are no more instructions for the Thread to execute. This is why I call a Thread, “a path of execution”.

Every program you run creates a Process and each Process is given an initial Thread. Threads have the ability to create more Threads. All these different Threads run independently of each other and scheduling decisions are made at the Thread level, not at the Process level. Threads can run concurrently (each taking a turn on an individual core), or in parallel (each running at the same time on different cores). Threads also maintain their own state to allow for the safe, local, and independent execution of their instructions.

The OS scheduler is responsible for making sure cores are not idle if there are Threads that can be executing. It must also create the illusion that all the Threads (that can execute) are executing at the same time. In the process of creating this illusion, the scheduler needs to run Threads with a higher priority over lower priority Threads. However, Threads with a lower priority can’t be starved of execution time. The scheduler also needs to minimize scheduling latencies as much as possible by making quick and smart decisions.

To understand all of this better, it’s good to describe and define a few concepts that are important.

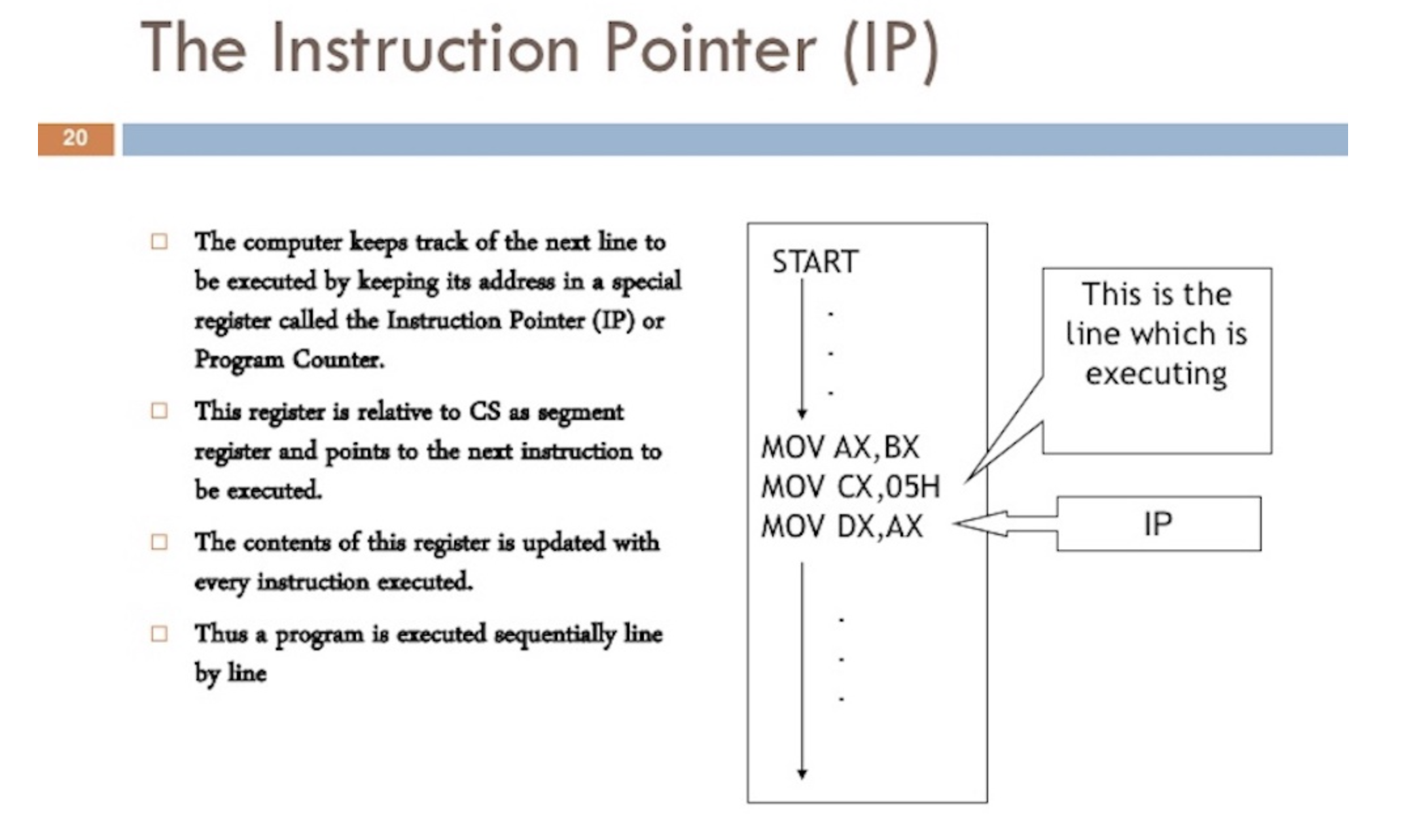

2. Program counter - PC#

The program counter (PC), which is sometimes called the instruction pointer (IP), is what allows the Thread to keep track of the next instruction to execute. In most processors, the PC points to the next instruction and not the current instruction.

3. Thread states#

Another important concept is Thread state, which dictates the role the scheduler takes with the Thread. A Thread can be in one of three states: Waiting, Runnable or Executing.

Waiting: This means the Thread is stopped and waiting for something in order to continue. This could be for reasons like, waiting for the hardware (disk, network), the operating system (system calls) or synchronization calls (atomic, mutexes). These types of latencies are a root cause for bad performance.

Runnable: This means the Thread wants time on a core so it can execute its assigned machine instructions.

Executing: …

4. Types of work#

There are two types of work a Thread can do. The first is called CPU-Bound and the second is called IO-Bound.

CPU-Bound: This is work that never creates a situation where the Thread may be placed in Waiting states. This is work that is constantly making calculations. A Thread calculating Pi to the Nth digit would be CPU-Bound.

IO-Bound: This is work that causes Threads to enter into Waiting states. This is work that consists in requesting access to a resource over the network or making system calls into the operating system. A Thread that needs to access a database would be IO-Bound. I would include synchronization events (mutexes, atomic), that cause the Thread to wait as part of this category.

The term CPU-bound describes a scenario where the execution of a task or program is highly dependent on the CPU. In contrast, a task or program is I/O bound if its execution is dependent on the input-output system and its resources, such as disk drives and peripheral devices.

5. Context switching#

If you are running on Linux, Mac or Windows, you are running on an OS that has a preemptive scheduler. This means a few important things. First, it means the scheduler is unpredictable when it comes to what Threads will be chosen to run at any given time. Thread priorities together with events, (like receiving data on the network) make it impossible to determine what the scheduler will choose to do and when. Second, it means you must never write code based on some perceived behavior that you have been lucky to experience but is not guaranteed to take place every time. It is easy to allow yourself to think, because I’ve seen this happen the same way 1000 times, this is guaranteed behavior. You must control the synchronization and orchestration of Threads if you need determinism in your application.

The physical act of swapping Threads on a core is called a context switch. A context switch happens when the scheduler pulls an Executing thread off a core and replaces it with a Runnable Thread. The Thread that was selected from the run queue moves into an Executing state. The Thread that was pulled can move back into a Runnable state (if it still has the ability to run), or into a Waiting state (if was replaced because of an IO-Bound type of request).

Context switches are considered to be expensive because it takes times to swap Threads on and off a core. The amount of latency incurrent during a context switch depends on different factors but it’s not unreasonable for it to take between ~1000 and ~1500 nanoseconds. Considering the hardware should be able to reasonably execute (on average) 12 instructions per nanosecond per core, a context switch can cost you ~12k to ~18k instructions of latency. In essence, your program is losing the ability to execute a large number of instructions during a context switch.

If you have a program that is focused on IO-Bound work, then context switches are going to be an advantage. Once a Thread moves into a Waiting state, another Thread in a Runnable state is there to take its place.** This allows the core to always be doing work. This is one of the most important aspects of scheduling. Don’t allow a core to go idle if there is work (Threads in a Runnable state) to be done. 还记得文章第一个加粗的那段话吗, OS Scheduler的作用, 然后再看看段句话,

If your program is focused on CPU-Bound work, then context switches are going to be a performance nightmare. Since the Thead always has work to do, the context switch is stopping that work from progressing. This situation is in stark contrast with what happens with an IO-Bound workload

6. Less is more#

In the early days when processors had only one core, scheduling wasn’t overly complicated. Because you had a single processor with a single core, only one Thread could execute at any given time. The idea was to define a scheduler period and attempt to execute all the Runnable Threads within that period of time. No problem: take the scheduling period and divide it by the number of Threads that need to execute.

As an example, if you define your scheduler period to be 1000ms (1 second) and you have 10 Threads, then each thread gets 100ms. If you have 100 Threads, each Thread gets 10ms. However, what happens when you have 1000 Threads? Giving each Thread a time slice of 1ms doesn’t work because the percentage of time you’re spending in context switches will be significant related to the amount of time you’re spending on application work.

What you need is to set a limit on how small a given time slice can be. In the last scenario, if the minimum time slice was 10ms and you have 1000 Threads, the scheduler period needs to increase to 10000ms (10 seconds). What if there were 10,000 Threads, now you are looking at a scheduler period of 100000ms (100 seconds). At 10,000 threads, with a minimal time slice of 10ms, it takes 100 seconds for all the Threads to run once in this simple example if each Thread uses its full time slice.

Be aware this is a very simple view of the world. There are more things that need to be considered and handled by the scheduler when making scheduling decisions. You control the number of Threads you use in your application. When there are more Threads to consider, and IO-Bound work happening, there is more chaos and nondeterministic behavior. Things take longer to schedule and execute.

This is why the rule of the game is “Less is More”. Less Threads in a Runnable state means less scheduling overhead and more time each Thread gets over time. More Threads in a Runnable state mean less time each Thread gets over time. That means less of your work is getting done over time as well.

7. Find the balance#

There is a balance you need to find between the number of cores you have and the number of Threads you need to get the best throughput for your application. When it comes to managing this balance, Thread pools were a great answer. I will show you in part II that this is no longer necessary with Go. I think this is one of the nice things Go did to make multithreaded application development easier.

Prior to coding in Go, I wrote code in C++ and C# on NT. On that operating system, the use of IOCP (IO Completion Ports) thread pools were critical to writing multithreaded software. As an engineer, you needed to figure out how many Thread pools you needed and the max number of Threads for any given pool to maximize throughput for the number of cores that you were given.

When writing web services that talked to a database, the magic number of 3 Threads per core seemed to always give the best throughput on NT. In other words, 3 Threads per core minimized the latency costs of context switching while maximizing execution time on the cores. When creating an IOCP Thread pool, I knew to start with a minimum of 1 Thread and a maximum of 3 Threads for every core I identified on the host machine.

If I used 2 Threads per core, it took longer to get all the work done, because I had idle time when I could have been getting work done. If I used 4 Threads per core, it also took longer, because I had more latency in context switches. The balance of 3 Threads per core, for whatever reason, always seemed to be the magic number on NT.

What if your service is doing a lot of different types of work? That could create different and inconsistent latencies. Maybe it also creates a lot of different system-level events that need to be handled. It might not be possible to find a magic number that works all the time for all the different work loads. When it comes to using Thread pools to tune the performance of a service, it can get very complicated to find the right consistent configuration.

8. Cache lines#

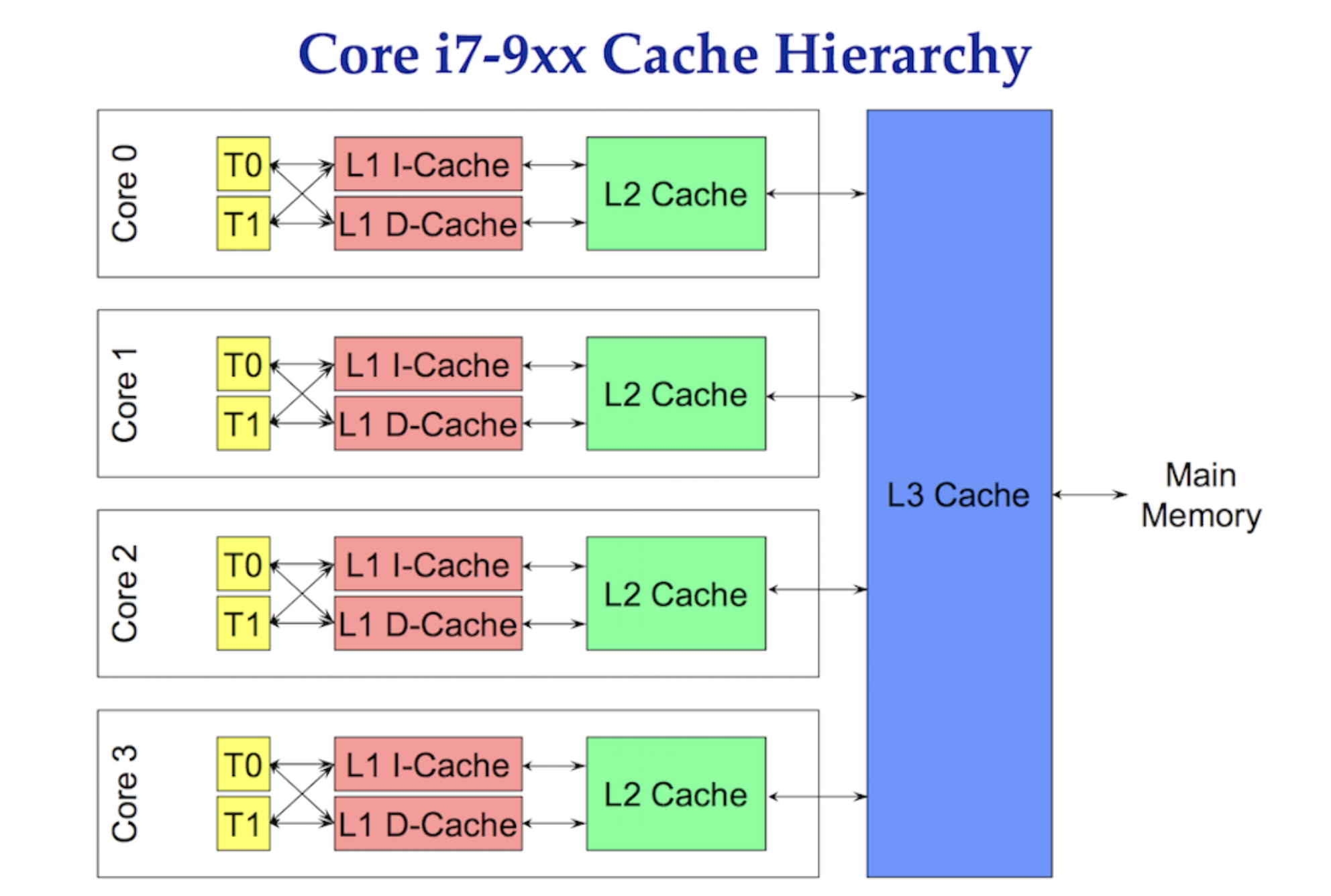

Accessing data from main memory has such a high latency cost (100300 clock cycles) that processors and cores have local caches to keep data close to the hardware threads that need it. Accessing data from caches have a much lower cost (340 clock cycles) depending on the cache being accessed. Today, one aspect of performance is about how efficiently you can get data into the processor to reduce these data-access latencies. Writing multithreaded applications that mutate state need to consider the mechanics of the caching system.

Data is exchanged between the processor and main memory using cache lines. A cache line is a 64-byte chunk of memory that is exchanged between main memory and the caching system. Each core is given its own copy of any cache line it needs, which means the hardware uses value semantics. This is why mutations to memory in multithreaded applications can create performance nightmares.

References:

Related articles:

多核 CPU 之 Hyper Threading | 橘猫小八的鱼