Value, Variable and Types - Go

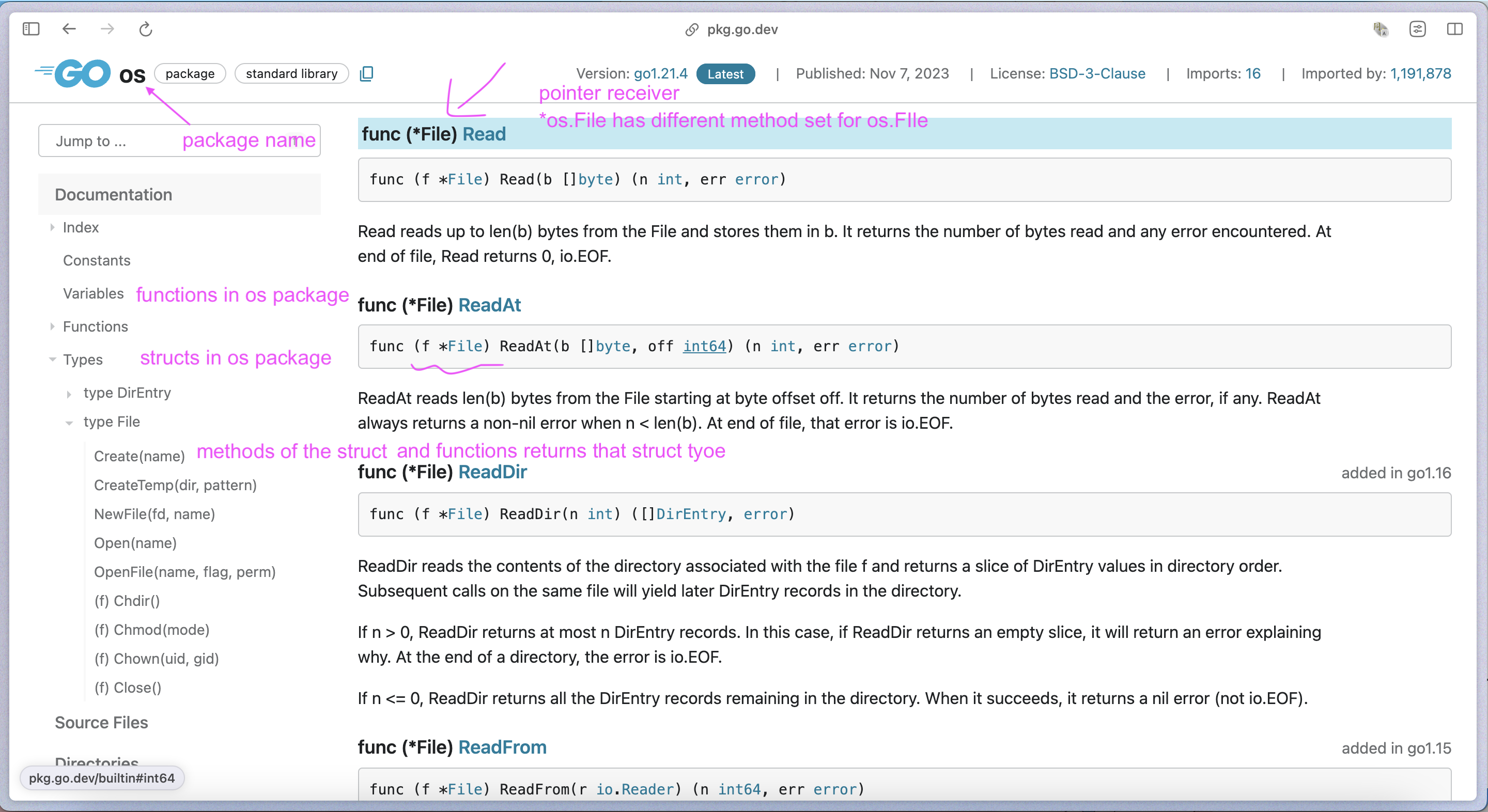

You should learn how to read the documentation provided Go, it’s very important:

1. static language#

Go is statically typed. Every variable has only one static type, that is, exactly one type known and fixed at compile time: int, float32, *MyType, []byte, and so on. If we declare

type MyInt int

var i int

var j MyInt

then i has type int and j has type MyInt. The variables i and j have distinct static types and, although they have the same underlying type, they cannot be assigned to one another without a conversion.

This is also true for an interface:

// Reader is an interface defined in io package

type Reader interface {

Read(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

Statically typed means that before source code is compiled, the type associated with each and every single variable must be known.

2. value & variable#

There is no object in Go, just variable and the value of a variable. We usually use variable and value as a same thing verbally.

I think is true in Go/C++/C : A variable is just an adress location. When assignments happens

str="hello world": Instead of telling the computer store this series of bits in 0x015c5c15c1c5, you tell him to store it instr.stris just a nicer name of a memory adress location.The computer doesn’t care and will replace them when compiling,

strwon’t exists, it’s all 0x015c5c15c1c5.Source: Does operator := always cause a new copy to be created if assign without reference?

3. reference-type vs value-type#

Keep in mind these two things:

-

There is just value-type in Go, no reference type, reference-type vs value-type is just for easy understanding and catagorizing, because reference is a very common concept in other languages like Java/Python.

-

Everything passed by value in Go.

- All copy is shallow copy, that is, only the value of the variable is copied, not the underlying data.

Go’s arrays are values. An array variable denotes the entire array; And everything passed by value, so when you assign or pass around an array variable you will make a copy of its all elements.

Slice is just a struct, it consists of three fields: a pointer to a underlying array, and its length and capacity. So When you assign or pass around a slice variable, the value of this variable is copied, but this is very cheap, just 3 words.

Did you catch that? All passed by value.

The terminology reference type has been removed from Go specification since Apr 3rd, 2013 (with the commit message: spec: Go has no ‘reference types’), the terminology is still popularly used in Go community. https://github.com/go101/go101/wiki/About-the-terminology-%22reference-type%22-in-Go

3.1. reference-type#

- A slice does not store any data, it just describes a section of an underlying array.

- Therefore, your function can return a slice directly or accept a slice as a argument.

- In Go, a string is in effect a read-only slice of bytes.

- Only use

*stringif you have to distinguish an empty string from no strings.

- Only use

- A map value is a pointer to a

runtime.hmapstructure.- A map is just a pointer itself, therefore, you don’t need returen a pinter of a map value.

- Like maps, channels are allocated with

make, and the resulting value acts as a reference to an underlying data structure. - Interface, a value of interface type is a pointer actually, not just a pointer, but consists of it.

- A variable of interface type stores a pair: the concrete value assigned to the variable, and that value’s type descriptor.

You don’t need to return a pointer to a reference-type for better performance.

3.2. value-type#

Actually, all are value-type in Go, but I’ll list some you may mistake them as reference-type:

- array

func main() {

arr_1 := [3]int{0, 0, 0}

arr_2 := arr_1

arr_2[0] = 99

arr_2[1] = 99

fmt.Println("arr_1:", arr_1)

fmt.Println("arr_2:", arr_2)

}

// output:

arr_1: [0 0 0]

arr_2: [99 99 0]

- struct

type Cat struct {

Name string

Age int

}

func main() {

cat_1 := Cat{

Name: "Coco",

Age: 1,

}

cat_2 := cat_1

cat_2.Name = "Bella"

fmt.Println("cat_1:", cat_1)

fmt.Println("cat_2:", cat_2)

}

// output:

cat_1: {Coco 1}

cat_2: {Bella 1}

As you can see, when do modification on cat_2, cat_1 is not affected.

4. value size#

| Kinds of Types | Value Size | Required by Go Specification |

|---|---|---|

| bool | 1 byte | not specified |

| int8, uint8 (byte) | 1 byte | 1 byte |

| int, uint | 1 word | architecture dependent, 4 bytes on 32-bit architectures and 8 bytes on 64-bit architectures |

| string | 2 words | |

| slice | 3 words | |

| pointer | 1 word | |

| map | 1 word |

NOTE: Here I call it value size not type size, this word is important, var a int, a is a variable/value whose type is int, and the size of this variable/value is 1 word on my arm64 cpmputer its size is 8 bytes.

5. how the size of a struct value is calculated?#

The size of a value means how many bytes the direct part of the value will occupy in memory. The indirect underlying parts of a value don’t contribute to the size of the value.

I’ll give you an example,

func main() {

cat := Cat{

name: "Coco",

age: 1,

s: []int{1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7},

}

fmt.Printf("cat: %T, %d\n", cat, unsafe.Sizeof(cat))

fmt.Printf("a.age: %T, %d\n", cat.age, unsafe.Sizeof(cat.age))

fmt.Printf("a.name: %T, %d\n", cat.name, unsafe.Sizeof(cat.name))

fmt.Printf("cat.s: %T, %d\n", cat.s, unsafe.Sizeof(cat.s))

}

cat: main.Cat, 48

cat.s: []int, 24

a.age: int, 8

a.name: string, 16

The sizes of two string values are always equal, same as string, the sizes of two slice values are also always equal. Values of a specified type always have the same value size.

Learn more: Go Value Copy Costs -Go 101

6. Variable declarations#

6.1. := vs var#

-

The

:=can only be used in inside a function, which is called short variable declarations. -

A

varstatement can be at package or function level, which is called regular variable declarations.

6.2. Zero value#

Variables declared without an explicit initial value are given their zero value. The zero value is:

0for numeric types,falsefor the boolean type, and""(the empty string) for strings.nilfor pointernilfor map and slice

func main() {

var i int

var f float64

var b bool

var s string

var p *string

var sl []int

var m map[string]string

fmt.Printf("%v %v %v %q %v %v %v \n", i, f, b, s, p, sl==nil, m==nil)

}

// 0 0 false "" <nil> true true

Dereferencing a nil pinter will cause panic, don’t do that.

kitten := Cat{Name: "Coco"}

// nil is zero value for a pointer

var cat *Cat

*cat = kitten // runtime error: invalid memory address or nil pointer dereference

6.3. var vs new vs make#

It’s a little harder to justify new. The main thing it makes easier is creating pointers to non-composite types. The two functions below are equivalent. One’s just a little more concise:

func newInt1() *int { return new(int) }

func newInt2() *int {

var i int

return &i

}

new() returns a pointer to the value it created, a pointer to map, channel and slice is thought as useless, so don’t use new() with these types, just use it with non-composite types. And always use make() when create slice, map and channnel.

When create a custom type, you can use literal:

type ListNode struct {

Val int

Next *ListNode

}

res := ListNode{}

res := &ListNode{}

Conclusion is that don’t use new(), it’s a little confusing, just use make() and var, :=

why new(): https://softwareengineering.stackexchange.com/a/216582

new vs make: https://stackoverflow.com/a/9322182/16317008

var vs make: https://davidzhu.xyz/post/golang/basics/003-collections/#5-var-vs-make

7. type conversions#

The expression T(v) converts the value v to the type T. Some numeric conversions:

var i int = 42

var f float64 = float64(i)

var u uint = uint(f)

Or, put more simply:

i := 42

f := float64(i)

u := uint(f)

Unlike in C, in Go assignment between items of different type requires an explicit conversion, this enchances the type safety of Golang.

8. Type assertions#

8.1. Basic syntax#

str := value.(string)

If it turns out that the value does not contain a string, the program will crash with a run-time error. To guard against that, use the “comma, ok” idiom to test, safely, whether the value is a string:

str, ok := value.(string)

if ok {

fmt.Printf("string value is: %q\n", str)

} else {

fmt.Printf("value is not a string\n")

}

similar syntax - 1:

users := make(map[string]int)

users["jack"] = 13

users["john"] = 15

user, ok := users["milo"]

if ok {

fmt.Println(user)

} else {

fmt.Println("no such user")

}

similar syntax - 2:

ele, ok:= <-channel_name

Type assertion provides access to an interface value’s underlying concrete value. So it only can be used when value’s type is interface:

var m map[interface{}]interface{}

_, isMap := m.(map[interface{}]interface{})

The snippet above will cause error: Invalid type assertion: m.(map[interface{}]interface{}) (non-interface type map[interface{}]interface{} on the left.

The code below works fine:

var m map[interface{}]interface{}

var t interface{}

t = m

_, isMap := t.(map[interface{}]interface{})

fmt.Println(isMap)

// print: true

8.2. use case#

func Copy(dst Writer, src Reader) (written int64, err error) {

return copyBuffer(dst, src, nil)

}

func copyBuffer(dst Writer, src Reader, buf []byte) (written int64, err error) {

// If the reader has a WriteTo method, use it to do the copy.

// Avoids an allocation and a copy.

if wt, ok := src.(WriterTo); ok {

return wt.WriteTo(dst)

}

// Similarly, if the writer has a ReadFrom method, use it to do the copy.

if rt, ok := dst.(ReaderFrom); ok {

return rt.ReadFrom(src)

}

...

}

bytes.Reader implements io.WriterTo interface and io.Copy uses that for optimized copying. source