HTTP 1.1 vs HTTP 2.0

1. HTTP/1.1#

The first standardized version of HTTP, HTTP/1.1, was published in early 1997, only a few months after HTTP/1.0.

HTTP/1.1 clarified ambiguities and introduced numerous improvements:

-

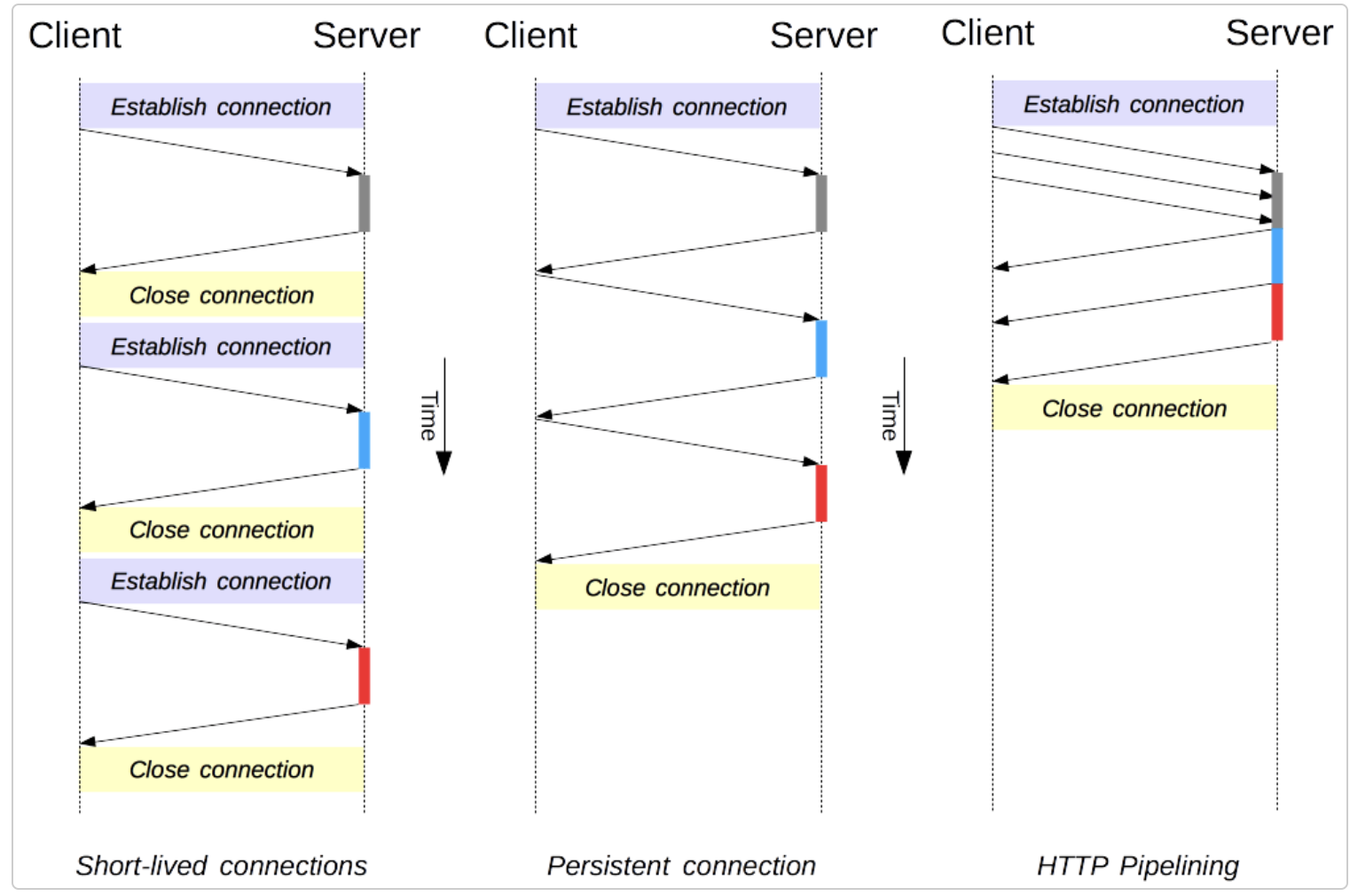

A underlying TCP connection could be reused. It no longer needed to be opened multiple times to request the resources embedded in the single original document.

- HTTP keep-alive, a.k.a., HTTP persistent connection, is an instruction that allows a single TCP connection to remain open for multiple HTTP requests/responses.

- Learn more: HTTP Headers (2) - David’s Blog

-

Pipelining was added. This allowed a second request to be sent before the answer to the first one was fully transmitted. This lowered the latency of the communication.

- Pipelining will cause another issue: Head-of-line (HOL) blocking, we will talk this later.

-

…

The persistent-connection model keeps connections opened between successive requests, reducing the time needed to open new connections. The HTTP pipelining model goes one step further, by sending several successive requests without even waiting for an answer, reducing much of the latency in the network. Connection management in HTTP/1.x | MDN

2. HTTP/2.0#

The primary goals for HTTP/2 are to reduce latency by enabling full request and response multiplexing, minimize protocol overhead via efficient compression of HTTP header fields, and add support for request prioritization and server push.

From a technical point of view, one of the most significant features that distinguishes HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2 is the binary framing layer, which can be thought of as a part of the application layer in the internet protocol stack. As opposed to HTTP/1.1, which keeps all requests and responses in plain text format, HTTP/2 uses the binary framing layer to encapsulate all messages in binary format, while still maintaining HTTP semantics, such as verbs, methods, and headers. An application level API would still create messages in the conventional HTTP formats, but the underlying layer would then convert these messages into binary. This ensures that web applications created before HTTP/2 can continue functioning as normal when interacting with the new protocol.

The conversion of messages into binary allows HTTP/2 to try new approaches to data delivery not available in HTTP/1.1, a contrast that is at the root of the practical differences between the two protocols.

3. HTTP/1.1 — Pipelining and Head-of-Line Blocking#

The first response that a client receives on an HTTP GET request is often not the fully rendered page. Instead, it contains links to additional resources needed by the requested page. Because of this, the client will have to make additional requests to retrieve these resources. In HTTP/1.0, the client had to break and remake the TCP connection with every new request, a costly affair in terms of both time and resources.

HTTP/1.1 takes care of this problem by introducing persistent connections and pipelining. With persistent connections, HTTP/1.1 assumes that a TCP connection should be kept open unless directly told to close. This allows the client to send multiple requests along the same connection without waiting for a response to each, greatly improving the performance of HTTP/1.1 over HTTP/1.0.

Unfortunately, there is a natural bottleneck to this optimization strategy. We said client to send multiple requests along the same connection (means a same thread on server), assume there are 3 request needed to be sent to server, one is for html, one is for an image and another one for a video. Now with persistent connections and pipelining, the client can send these three requests at a time within one TCP connection, and these requests will be procceeded by the server one by one (they are in a same tcp connection), if the second request is very time consuming at server, then the third request has to wait for the second finished. Adding separate, parallel TCP connections at client could alleviate this issue, but there are limits to the number of concurrent TCP connections possible between a client and server, and each new connection requires significant resources.

Head of Line blocking in HTTP terms is often referring to the fact that each browser/client has a limited number of connections to a server and doing a new request over one of those connections has to wait for the ones to complete before it can fire it off. The head of line requests block the subsequent ones. HTTP/2 solves this by introducing multiplexing so that you can issue new requests over the same connection without having to wait for the previous ones to complete.

HTTP/2 does however still suffer from another kind of HOL, namely on the TCP level. One lost packet in the TCP stream makes all streams wait until that packet is re-transmitted and received. This HOL is being addressed with the QUIC protocol…

Learn more: https://stackoverflow.com/a/45583977/16317008

The multiplex here is not the multiplex on linux (epoll, select), learn more: HTTP 2.0 Binary Framing - David’s Blog

4. What are the other differences between HTTP/2 and HTTP/1.1 that impact performance?#

Multiplexing: HTTP/1.1 loads resources one after the other, so if one resource cannot be loaded, it blocks all the other resources behind it. In contrast, HTTP/2 is able to use a single TCP connection to send multiple streams of data at once so that no one resource blocks any other resource. HTTP/2 does this by splitting data into binary-code messages and numbering these messages so that the client knows which stream each binary message belongs to.

Server push: Typically, a server only serves content to a client device if the client asks for it. However, this approach is not always practical for modern webpages, which often involve several dozen separate resources that the client must request. HTTP/2 solves this problem by allowing a server to “push” content to a client before the client asks for it. The server also sends a message letting the client know what pushed content to expect – like if Bob had sent Alice a Table of Contents of his novel before sending the whole thing.

Header compression: Small files load more quickly than large ones. To speed up web performance, both HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2 compress HTTP messages to make them smaller. However, HTTP/2 uses a more advanced compression method called HPACK that eliminates redundant information in HTTP header packets. This eliminates a few bytes from every HTTP packet. Given the volume of HTTP packets involved in loading even a single webpage, those bytes add up quickly, resulting in faster loading.

References: